The first 43

I recently received copies of two articles written by Dr. Edwin Lewis Stephens (founder of the Live Oak Society) for the Louisiana Conservation Review (a discontinued publication of the Louisiana Department of Conservation). Many thanks to Dr. Bruce Turner and Jane Vidrine of the Special Collections Division at the Edith Garland Dupré Library at the University of Louisiana, Lafayette for their help in getting copies of these articles. (They are posted under the “Pages” heading in the right table of contents column of the blog. When the page opens just click on the title and it will open a photocopy of the original article.)

The first article titled, “I Saw In Louisiana a Live Oak Growing,” contains the original proposal by Dr. Stephens to establish an organization comprised entirely of live oak trees that were 100 years of age or older (now called The Live Oak Society). The article’s title is borrowed from a Walt Whitman poem of the same name. This article, dated April 1934, marks the founding of the Live Oak Society in Louisiana and the South.

The second article is titled “The Live Oak Society.” In it, Dr. Stephens discusses the reactions and comments he received from his previous article and recommendation to form the Live Oak Society.

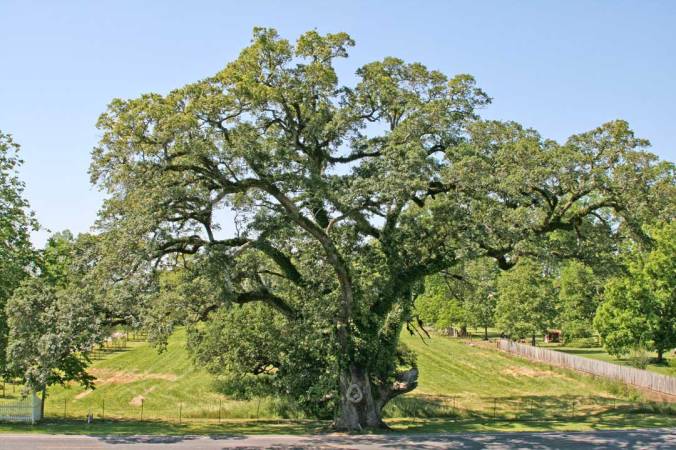

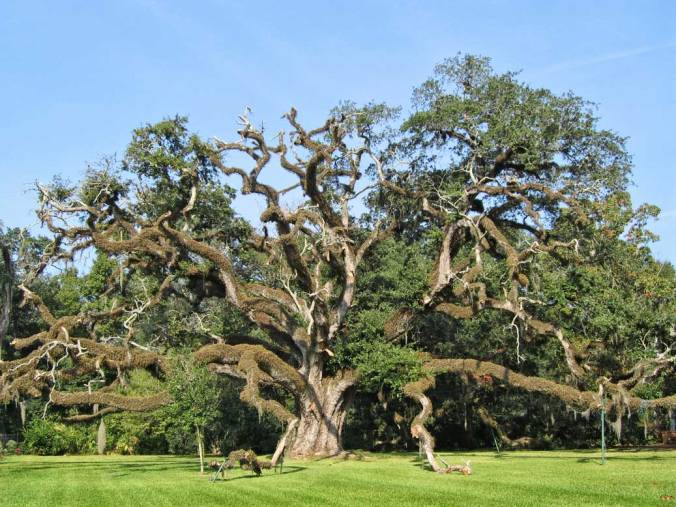

Stephens’ appreciation for live oaks grew over many years of living in Louisiana and from frequent motor trips he took with his wife along the back roads and byways through Cajun country. Influenced by his background as a science teacher, he observed, measured, photographed, and collected data on the oaks, taking special interest in the oldest and largest of the species.

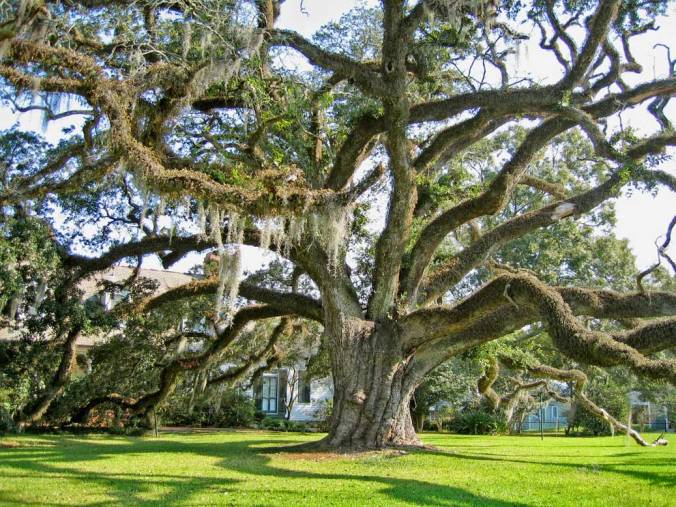

From his perspective as a scholar and poet, he recognized the deeper truth of this Southern icon—that more than any other aspect of the landscape, the live oak symbolically reflects the most memorable and distinctive characteristics of the cultures and people that settled this rich alluvial region: strength of character, forbearance, longevity, and a hearty nature.

Stephens wrote, “To my mind the live oak is the noblest of all our trees, the most to be admired for its beauty, most to be praised for it strength, most to be respected for its majesty, dignity and grandeur, most to be cherished and venerated for its age and character, and most to be loved with gratitude for its beneficence of shade for all the generations of man dwelling within its vicinity.

…I suggest that the members of the Association shall consist of trees whose age is not less than a hundred years. I at present number among my personal acquaintance forty-three such live oaks in Louisiana, eligible to qualify for charter membership.” Seventy-four years later, the Live Oak Society counts more than 7,000 member oaks on its registry in 14 states (and now includes Junior League trees with a girth of at least eight feet).

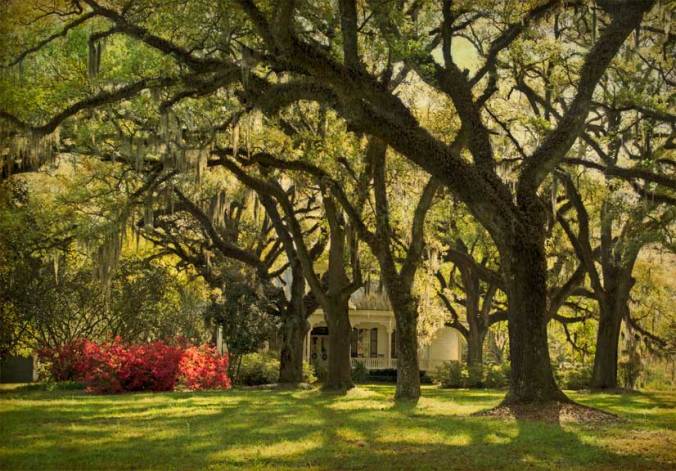

In 2008, I wrote an article for the American Forests magazine in which I attempted to locate and photograph as many of the original Live Oak Society inductees as I could locate. Using Dr. Stephens’’ 74-year-old article as a guide, I began retracing his drives across South Louisiana, along bayous with names like Teche, Lafourche, Maringouin, Grosse Tete, and Terrebonne—French and native American names that evoke romantic images of moss-draped trees, Cajun fisherman in flatboats, sultry heat, and white-columned plantation homes. Dr. Stephens listed the 43 charter oaks in order of their size—large to less large—noting their circumference, name (usually that of a sponsor), and general location.

I quickly realized that I was naïve about the degree of change that can occur in a landscape over 74 years. Plantation homes have faded away, changed names, been parceled off and subdivided, or simply torn down. Properties have changed owners and entire families have died or moved away.

In some cases, oaks have been registered more than once, and by different owners, adding to the confusion between Dr. Stephens description of a tree’s location and the current landscape. Some oak names were familiar to a few locals and were not particularly difficult to find. Others required extensive research through libraries, the Internet, books and the kind assistance of many local librarians, chambers of commerce, sheriff’s deputies and Louisiana Garden Club members across the state.

Thomas Boyd Oak and state capital; 20′ 6″ (#38 of 43) the tree fell down in Hurricane Gustave and has been removed.

I confirmed that in just 74 years four of the inductees had died including the top three. I suspected that six more were deceased possibly due to urban growth and development (a total of 14%). Of the original 43, I found nineteen oaks (45%) alive and well. I was unable to locate or accurately confirm the identity of fourteen more (but suspect they are still alive).

Since 2008 when I wrote the American Forests article, I continued my search for the rest of the 43 whenever I’m photographing in an area where they were located. At some point soon, I will publish an update that will include any other of the original inductees I have been able to accurately identify and document.

Each year, thousands of tourists visit St. Martinville, Louisiana, in search of the roots of Cajun culture—to experience the food, music, and to visit the places associated with the story of Evangeline. The Evangeline oak is undoubtedly the most famous oak in Louisiana, though oddly it’s not a very old or exceptionally large tree. And according to some sources, it’s the third oak in the St. Martinville area that has been designated as the “oak under which the Cajun lovers Emmeline and Louis were reunited” after their long separation when the Acadians were exiled from Canada. (Emmeline and Louis are reported to be the real-life characters upon which Longfellow’s fictitious Evangeline and Gabriel were modeled.)

Each year, thousands of tourists visit St. Martinville, Louisiana, in search of the roots of Cajun culture—to experience the food, music, and to visit the places associated with the story of Evangeline. The Evangeline oak is undoubtedly the most famous oak in Louisiana, though oddly it’s not a very old or exceptionally large tree. And according to some sources, it’s the third oak in the St. Martinville area that has been designated as the “oak under which the Cajun lovers Emmeline and Louis were reunited” after their long separation when the Acadians were exiled from Canada. (Emmeline and Louis are reported to be the real-life characters upon which Longfellow’s fictitious Evangeline and Gabriel were modeled.) The Evangeline Oak is located on the edge of Bayou Teche at the foot of East Port St., next to the Old Castillo Bed and Breakfast (which I can personally state is very haunted—but that’s another story!).

The Evangeline Oak is located on the edge of Bayou Teche at the foot of East Port St., next to the Old Castillo Bed and Breakfast (which I can personally state is very haunted—but that’s another story!).