Pretty much everyone knows of the oak allée at Oak Alley Plantation in Vacherie – the Grand Dame of live oak allées on Louisiana’s historic River Road. It’s the classic, iconic, most visited, and most photographed allée of live oaks in the South. (Their new photo book documents this fact.) But plantation country along historic River Road has several lesser-known oak allées that are, to this photographer, each as beautiful and memorable in their own way.

In this post, I’ll feature the first two of four other oak allées that a visitor can enjoy, all within approximately 15 miles (as the crow flies) of Oak Alley Plantation. One is accessible through a paid tour (at Whitney Plantation, Evergreen is now closed to visitors since 2020) and one can be viewed easily from the east bank side of River Road, on Hwy. 44 near Convent (the St. Joseph allée at Manresa House of Retreats).

The Two Oak Allées at Evergreen Plantation

Quarters allée at Evergreen, view from mid-allée

The Quarters Allée is the older of the two oak allées at Evergreen Plantation. It’s the one that’s hidden from passersby on the west-bank side of River Road (LA Hwy. 18). To view and explore both of Evergreen’s oak allées, you must take a guided tour of the plantation, but the experience (and photo opportunities) are well worth it. (NOTE: Unfortunately, Evergreen Plantation is closed to tours for the foreseeable future, due to the Covid pandemic. Researchers may visit their archives by appointment.)

In my opinion, the 90-minute guided tours at Evergreen are (were) the best that River Road has (had) to offer. One reason is the experience of walking through the historic slave community and stepping into some of the empty cabins. Other River Road plantations may have one or two original slave cabins that date from the antebellum period. Most have moved structures from elsewhere or built new structures to recreate the semblance of a slave community to help illustrate their tour narratives of the slave experience.

Six cabins, east row of historic slave quarters

At Evergreen, the original intact quarters community of 22 cabins have been preserved and maintained from the 1830s to the present day. These cabins were lived in first by enslaved individuals and then plantation workers through the Civil War, through emancipation, reconstruction, and the Great Depression, until the early 1950s when its inhabitants were finally moved out.

Older oaks with Spanish moss, at the front of the quarters allée, mid-day light

The quarters allée begins with a group of a dozen older oaks growing behind the overseer’s house, upriver from the main house. These older oaks are roughly the same age as several large oaks growing along the front of the Evergreen property and flanking the parterre garden behind the manor house. These larger oaks were planted probably in the late 1700s or early 1800s when the first structures were built on this site.

Down the dirt road and past a cypress fence that separates the front and back of the plantation, the quarters oak allée proceeds into, and through, the center of the plantation’s slave quarters. In the heart of the quarters’ community, the presence of the past is almost tangible. Bordering the dirt road and inside the line of 22 slave cabins, approximately 72 oaks make up the quarters’ allee. The oak trees were planted circa 1860, according to Evergreen curator Jane Boddie. These trees were a functional part of the slave community and provided shade and protection from the elements for its residents.

Slave quarters and allée, mid-day sun

There is evidence that the majority of the quarters’ cabins were built during an 1830–1840 remodel and expansion of the plantation by Pierre Clidament Becnel. He purchased the property from his grandmother, Magdelaine Haydel, in 1830, and began an ambitious Classical Greek Revival renovation of his grandmother’s two-story Creole cottage home and outbuildings. Becnel added the signature front double-return staircase to the home and the Greek-Revival garconnieres, pigeonniers, kitchen, guesthouse, and privy around the main complex.

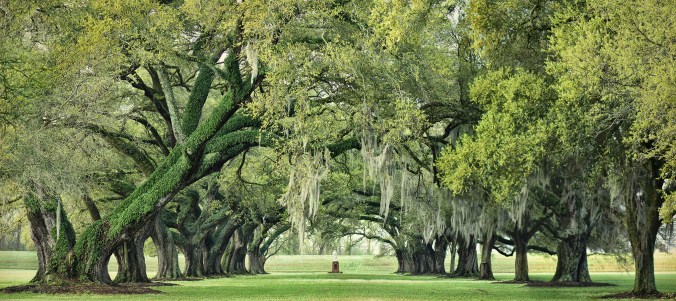

Farm road allée at Evergreen Plantation, view from farm road gate.

The Farm Road Allée – The second allée of oaks at Evergreen is located just upriver from the main house and overseer’s cottage and can be glimpsed as one drives past, going up or downriver past Evergreen’s grounds. The farm road entrance off of River Road presents the viewer with a dramatic half-mile long arched tunnel of live oaks lining the dirt road that leads to the farming operations at the rear of the plantation. The trees were moved from another nearby plantation and planted in the 1950s, making them about 70-80 years old.

Evergreen farm road allée, afternoon light

The farm road allée was planted under the direction of Ms. Matilda Gray, who purchased Evergreen in 1944 after it had been abandoned in the early years of the Depression. Under Ms. Gray’s supervision, Evergreen was renovated to restore the buildings and grounds to their former beauty. After her death in 1971, her niece, Mrs. Matilda Stream, inherited Evergreen and has continued to maintain the historic property and protect it from encroachment by local industries.

Both of Evergreen’s oak allées can be explored currently only by historic researchers. Contact the plantation online at www.evergreenplantation.org or by calling 985-497-3837.