We’re nearing the end of my original list of live oaks that I compiled with 30-plus-feet girth. In my search, I identified approximately 20 live oaks in the Live Oak Society registry that had a stated trunk circumference of 30 feet or more (at 4.5’ off the ground). A few of those were originally mis-measured by their owner/sponsors; so my current list (almost final list) now contains 14 oaks larger than 30 ft. in girth, six oaks with girths of more than 29 ft., and a few more that I’ve yet to locate with girths reportedly larger than 29 ft. (You can see my current list at the end of this blog entry.)

However, I fully suspect to add more oaks to this list in the coming year. In the process of working on this project, we’ve relocated back to Louisiana (I grew up here) to be better able to continue the 100 Oaks Project. Cyndi and I are now living in the old Constant family home outside of Thibodaux where we have a 25’-8” and a 21’-6” oak in the front yard. (The Constants were old family friends of my parents in Thibodaux, and I found their home for rent while photographing the oaks on their property).

Constant/Faucheaux Oak (21′-6″) in foreground; Faucheux Oak in background (25′-8″)

We’ve also made new friends with several garden club groups across the state, including the Lafourche and Terrebonne parish garden clubs and master gardeners group (Cyndi was a master gardener in Texas and is now taking classes to become certified in Louisiana). The Lafourche and Terrebonne groups have been working hard to register old live oaks in their area—we applaud the great work they’ve done.

Now on to the trees…

Grosse Tete Oak, color study 1 (30′-2″)

One of the easiest 30-something oaks to locate is the Grosse Tete Oak. You can spot it on the north side of the I-10 overpass at the Highway 77 Grosse Tete / Rosedale exit. There are several lovely old oaks nearby on the grounds of the Iberville Parish Visitor Center, located on the LA. Hwy. 77 side of the bayou, right near the exit. The Grosse Tete Oak is just south of the Visitor Center.

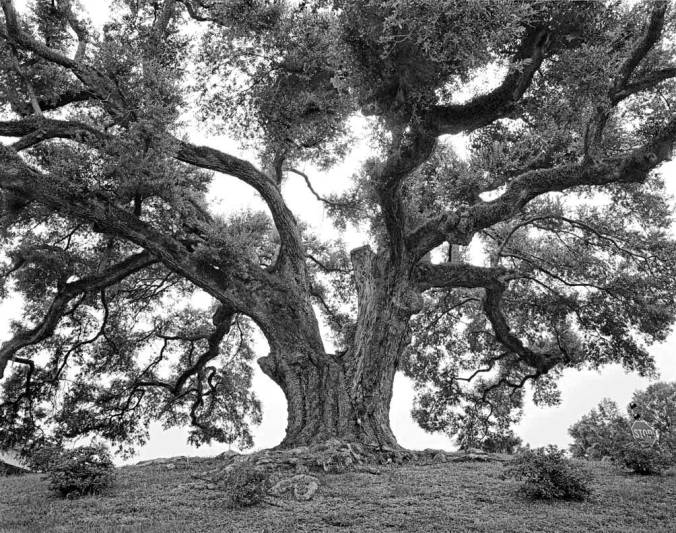

Grosse Tete Oak, b&w study 2

Grosse Tete Oak, infrared study 3

This grand old tree is number 17 on the list of the 43 charter oaks in the Live Oak Society (or number 22 on their current online list). When listed in Dr. Stephen’s Louisiana Conservation Review article of 1934, it had a girth of 22 ft. 6 in. Our most recent measurement in September 2015 shows it with a girth of 30 ft. 2 in.

The Grosse Tete Oak’s original sponsor was Mrs. Lelia Barrow Mays. Both “Barrow” and “Mays” are family names that are significant in local history.

Grosse Tete is a small village with a current population of 647 (according to their website). Much of the village is spread along a two-mile stretch of businesses and homes on both sides of Bayou Grosse Tete (which means “Big Head” in French). Local legend (and the Grosse Tete website) states that the name came about from a big-headed Choctaw Indian who lived and hunted in the area when it was settled by French Acadians. Before the railroad, the bayou was the main route of transportation through this pastoral region of lush green pastures and sugarcane fields.

The Mays Oak, #6 of 43 Live Oak Society charter member trees.

The Mays Oak (30′-11″) is number six (6) of the original 43 charter members of the Live Oak Society. It’s located just a short drive north on LA Hwy. 77 from Grosse Tete on the grounds of Live Oaks Plantation. The plantation home is on the east side of Hwy. 77, facing Bayou Grosse Tete, and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It’s a private home and not open to the public.

According to the KnowLa website (an online encyclopedia of Louisiana sponsored by the Louisiana Endowment of the Humanities), Live Oaks Plantation was built in 1838 by Charles H. Dickinson. He and his 14-year-old bride, Anna Turner, moved to Louisiana from Tennessee in 1828, almost two dozen years after his father died in a duel with Andrew Jackson in 1806. With the help of slave artisans, he built the two and one-half story plantation house of pegged local cypress and bricks made from clay from the area.

Mays Oak study with brick tomb

The historic oak is located to the left of the plantation home (viewed from the highway) and next to an unusual brick tomb and brick church that was once used by plantation slaves. Later the church served as a schoolhouse and Episcopal chapel (both structures can be seen in the color photo above, and the tomb can be seen in the black and white photo to the left).

The brick tomb contains iron caskets cast in the form of a human body. The Smithsonian Institution dated the caskets in the tomb to circa 1830.

For more information about Live Oaks Plantation, go to KnowLa.org (a great resource on historic info about Louisiana) or look for Karen Kingsley’s book, Buildings of Louisiana published by Oxford University Press, 2003.

My current list of 30-something-size live oaks (as of 2016)

1. Seven Sisters Oak – Lewisburg / Mandeville; 39′-10″

2. Randall Oak – New Roads; 35′-8″

3. Edna Szymoniak Live Oak – LSU Hammond Research Station; 35′-6″

4. Lorenzo Dow Oak – near Pine Grove, LA; 35′- 8″

5. La Belle Colline Oak – Between Sunset and Carencro; 34′

6. The Martin Tree – Gonzales, LA, Ascension Parish; 34′

7. The Governor’s Oak – Baton Rouge; 33′-3″

8. Lastrapes Oak (Seven Brothers Oak) – Washington, LA; 32’-3″ (largest section)

9. Rebekah Oak – Breaux Bridge; 32′

10. Boudreaux Friendship Oak – Lafayette; 31’-10”

11. Lagarde Oak – Luling; 30′-11″

11. Mays Oak – Live Oaks Plantation, near Rosedale; 30′-11″

12. Blanchet Oak – Lafayette; 30′-7″

13. Grosse Tete Oak – Bayou Grosse Tete; 30′-2″

14. Etienne de Bore’ Oak – Audubon Park, NOLA; 30’ (also called the Tree of Life and the Monkey Hill Oak)

29 foot-plus oaks

15. Josephine A. Stewart Oak – Oak Alley Plantation; 29′-11″

16. Hudson Oak – Hudson Oaks home, Prairieville, LA; 29′-9″

17. Grenier Oak – above Thibodaux on Hwy. 1; 29’-?”

18. Stonaker or St. Maurice Oak – New Roads, LA; 29′-6″

19. St. John’s Cathedral Oak – Lafayette; 29’-6″

20. Mr. Mike Oak – Oaklawn Manor, near Franklin; 29′

Yet to locate and photograph

22. Ole Oakie – St. Martinville; 32’-2” (Kennison Ambrose, sponsor)

23. Grandpere Oak – Barataria Bayou, Jefferson Parish; reportedly 29’-4”

24. J. H. Lewis Oak – St. Louis Plantation, Whiteville, LA; 29’+