With a list tools and resources that can help you create a tree ordinance for your town or community. (See Resources Section, bottom of page)

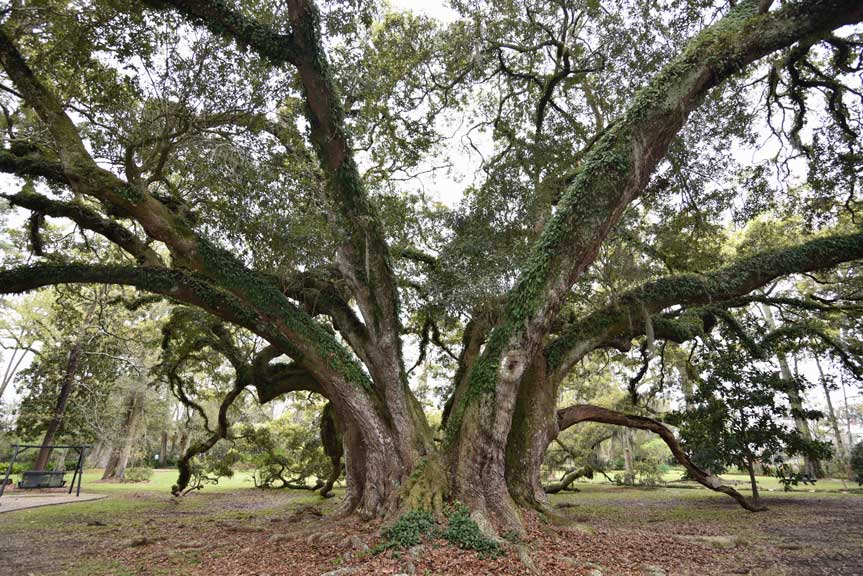

The situation. I’ve received several emails in recent months from individuals desperately looking for information on how they can save a treasured old oak in their community from removal. The circumstances were all sadly similar. In each case, a developer, or individual had purchased the land on which an old or historic oak (or oaks) had been growing, possibly for centuries, but certainly for long enough that the tree had become a much-loved part of local history and culture.

Yet, the new landowner could only see an old tree that was in the way—of a new hotel, housing development, roadway, or real-estate expansion of one form or another. In some cases, an arborist had been hired (by the developer) to give an opinion that the tree was very “old” and possibly even declining in health.

In most cases, the tree was named after a well-known individual and had even been registered with the Live Oak Society as a sign of its importance to those who cared for it and lived around it. The question I got repeatedly was, “certainly, there must be some law protecting a ‘registered’ tree from being cut down?”

Unfortunately, registering an oak with the Live Oak Society or any other local organization provides no legal protection for a tree from its removal. Registering a live oak is only a first step to recognizing an oak as a notable and loved part of a community. Registration is a good idea because it makes people aware of the historical significance of the tree, but unless your community, town, county commission, or other law-making body has created an ordinance or code to protect elder live oaks or other historic trees, then your oak may have no legal protection from the chainsaws of progress and development.

There are rare cases in Louisiana where oaks have been saved. These are situations that I know of in Louisiana where individuals have joined together with neighbors and friends, petitioned local leaders, and raised enough public support (and interest) to save specific trees from being cut down.

The Mr. Al Oak. In 2009, a 150-year-old live oak tree named “Mr. Al” was saved from certain death by a group of local citizens in the New Iberia area. The old oak was slated for removal by the Department of Transportation and Development (DOTD) as part of a frontage road construction project on State Hwy. 90. The property owner, Kelli Peltier, called friends and began a petition to save Mr. Al. With the help of local organizations and concerned citizens, as well as support from an ex-governor of Louisiana, the DOTD chose to move the old oak rather than cut it down. (You can read the whole story here.)

Old Dickory Oak. In 2003, neighborhood citizens in Harahan, with the help of The Live Oak Society chairperson Coleen P. Landry, were able to convince the DOTD to reroute the road improvements around the old oak. Landry and the Society also played a role in saving a stand of 13 live oaks near Jeanerette threatened by highway construction by appealing directly to then-governor Bobby Jindal to help save the oaks.

The Youngsville Oak. In another case in which an old historic oak was slated to be removed to make way for a new traffic circle along state Hwy. 92 in Youngsville, local citizens with the help of Trees Acadiana, a local tree-preservation organization, raised enough local support (through the local press and well-known artist George Rodrigue) to convince public officials to spare the tree. The common thread in each of these stories is local support.

Steps to take to save a tree.

1. If an important oak tree in your neighborhood or community is in immediate danger of removal, the first step is to make loud positive noise.

Start a petition, get help and support from local clubs, tree-friendly organizations, and gardening groups, as well as the local media. Create a story of the human history of the old tree and emphasize why it’s important to your community’s cultural and historical identity to save the tree. Appeal to your local city council, commissioners, and mayor as well as state-level politicians. Make a strong “positive” argument for these decision-makers to gain their support. A positive argument is important. Look for a win-win solution, and other options for the new property / tree owner, Highway Department, or developer that will make it worth their while to spare the tree. In the process, they’ll create good feelings, positive publicity, and positive relationships with the community. There’s always a positive benefit for both sides by saving a tree.

Not sure how to start a petition? Here are two websites that can help you start a petition online and get it distributed to your community.

• Petitions.net – This site lets you create a professional petition online, gather signatures, and present your results to decision-makers. It’s free and easy to use.

• Change.org – This website is run by a non-profit and though the petition function they offer is also free and easy to use, they also offer help to review and tweak your petition wording to make the strongest possible message. A donation is requested for this service that is well worth it.

2. Prepare now. Talk to your local garden clubs and find out what laws or ordinances your town or city may have in place already. Does your town have a town or city arborist? Contact that person. He or she can provide guidance on what to do. Most cities in the U.S. have some sort of ordinance that provides guidelines for the removal of large and old trees. Your next step is to get your local ordinance or codes amended or supplemented to include protection for historic, notable, or significant trees. Take steps to establish legal protections now, before a favorite old tree is threatened.

YOU CAN CHANGE LOCAL LAWS AND CREATE A LOCAL TREE ORDINANCE

Developing A Tree Ordinance – Reference Materials, Publications, Books, and Tools

Guidelines for Developing and Evaluating Tree Ordinances

Tree City USA has created a guide, “How to Write a Tree Ordinance” (a downloadable PDF can be found here). This guide provides a model that you can follow to draft and establish a “tree management ordinance” for both small and large communities in Louisiana or elsewhere.

Tree Ordinance Software

Unique software for cities is available to help them develop ordinances that will ensure the future of their community forests. TreeOrd, an interactive CD-ROM, was developed by the Tree Trust with a grant from the USDA Forest Service. The cost is $60 plus shipping and handling. http://www.mnstac.org/RFC/tree_order_form.PDF

Tree Ordinance Development Guidebook

Georgia Forestry Commission http://www.gfc.state.ga.us/CommunityForests/documents/2005TreeOrdinance-100.pdf

Landscape Ordinances Research Project

A resource home page for urban design, city planning, urban forestry, site design, landscape architecture, architecture, site engineering, land use law and land development–highlighting legal standards and technical requirements for site development plan

http://www.greenlaws.lsu.edu/sitemanager.htm

U.S. Landscape Ordinances: An Annotated Reference Handbook

by Buck Abbey, D. Gail Abbey

This comprehensive reference brings together and explains the planning ordinances which govern the landscapes of 300 U.S. cities. In it, the author demystifies the complex planning laws that regulate such areas as the design of parking lots, vehicular use areas, landscape buffers, and tree plantings.

Guide to Developing a Community Tree Preservation Ordinance

Presented by the Community Tree Preservation Task Force of the Minnesota Shade Tree Advisory Committee, this guide describes the planning process, typical ordinance elements, and resources available for the task.

http://www.mnstac.org/RFC/preservationordguide.htm

Guide to Writing a City Tree Ordinance – Model Tree Ordinances for Louisiana Communities

http://www.greenlaws.lsu.edu/modeltree.htm

Research Article – Kathleen Wolf

http://www.cfr.washington.edu/research.envmind/Roadside/Trees_Parking.pdf

Developing a Successful Urban Tree Ordinance

Charles C. Weber, Alabama Forestry Commission

Tree City USA Bulletin #9 How to Write a Municipal Tree Ordinance National Arbor Day Foundation http://www.arborday.org/programs/treecitybulletinsbrowse.cfm

Tree City USA Bulletin # 31 Tree Protection Ordinances National Arbor Day Foundation http://www.arborday.org/programs/treecitybulletinsbrowse.cfm

Guidelines for developing urban forest practice ordinances

Bell, P.C., Plamondon, S., and Rupp, M.

Oregon Department of Forestry, Forest Practices Program, Urban and Community Forestry Program. This guide is designed to assist cities and counties in the development of urban forest practice regulations.

http://www.oregon.gov/ODF/URBAN_FORESTS/docs/Other_Publications/UrbanFP.pdf

Urban and community forestry: A guide for the Northeast and Midwest United States

Ascerno, M. et al.

U.S. Forest Service, Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry. 216 pp. + appendix. 1992.

This manual updates a 1990 edition which focused on the interior western region of the U.S. Includes chapters on history, benefits (aesthetic, social, recreational, wildlife, economic, and physical), programs, inventories, planning, ordinances and policy, site evaluation, tree selection and planting, soils, and maintenance. Undated; probable publication date, 1992.

Municipal tree manual

Hoefer, P.J., Himelick, E.B., and DeVoto, D.F.,

Urbana, IL, International Society of Arboriculture. 42 pp.

Prepared in cooperation with the Municipal Arborists and Urban Foresters Society. The purpose of this manual is to be a guide for preparing new, or revising old, municipal tree ordinances.

Community trees: Tree Ordinances for Iowa communities

Wray, P.

Iowa State University, Cooperative Extension Service http://www.extension.iastate.edu/Publications/PM1429b.pdf

Sample Ordinances from Cities and Towns

There are several on-line ordinance clearinghouses. All of these publishing services make it easy to search for specific words or phrases within a given ordinance using a “search” feature.

General Code Publishers

www.generalcode.com/webcode2.html

LexisNexis Municipal Codes

http://municipalcodes.lexisnexis.com

American Legal Publishing Corporation

http://www.amlegal.com/library

Municipal Code Corporation

www.municode.com http://www.municode.com/resources/code_list.asp?stateID=49

Post-publication addition to this post: I’m heartened to read two different stories today in newspapers in North Carolina and Florida where the communities started petitions to save old oaks from being removed to make way for new development. These stories are new, as of the day I’m writing this, but the petitions got the attention of both their local government officials and the news media. That’s the way change starts, many voices being raised to create laws to protect historic trees and urban forests and to reconsider the importance of oaks and other trees to the health and well-being of a community.