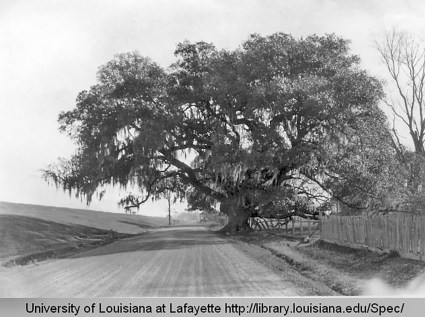

Lastrapes Oak, Afternoon Light, Washington, LA

On a recent visit to Louisiana, I took a side road off of the Interstate Hwy. to visit the small town of Washington and the Lastrapes (or Seven Brothers) Oak. Located about a mile out of town on State Highway 182, the large old oak still stands proudly and is well-maintained by the Lastrapes family who still owns the property on which the oak grows. When I stopped to re-photograph the tree, there was a work crew doing maintenance on the fence (shown behind the tree in the photo above).

The Lastrapes Oak is the seventh tree listed in Dr. Edwin L. Stephens’ 1934 magazine article in the Louisiana Conservation Review. It is one of the original 43 member trees in the Live Oak Society and is #9 on the Live Oak Society’s registry, which contains a growing list of more than 10,000 member trees. Even my panoramic photograph hardly gives an idea of the massive size and girth of the unusual multiple trunks of this old oak. The main trunk is more than 33 feet in circumference. The largest secondary trunk is almost 30 feet around at a height of 4 feet. This beautiful old tree is one of my favorite live oaks in Louisiana and is surely a monument of a different kind.

The Seven Brothers’ name supposedly came from a story that said the tree was named for seven Lastrapes brothers who had left home to fight in the Civil War. Another variation of the story, described in Ethelyn Orso’s Louisiana Live Oak Lore, claimed that the birth of his seventh son prompted Jean Henri Lastrapes to request that seven oaks be planted; the workers arrived late in the day with the seedlings and temporarily put them in one container (or hole). The business of the days that followed in the cotton fields distracted the workers from ever completing the planting task—and thus the trees grew together, sharing the close proximity of their original planting site. For a complete story of the tree’s history, you can read my original post in this blog.

Whichever story is accurate, the tree is more appropriately referred to today as the Lastrapes Oak, after the family who has owned the property where it resides for several generations and takes pride in caring for the well-being of the historic oak. It is one of the best-maintained ancient oaks in Louisiana.

(Prints of all photos in my blog are available for purchase. For information, email bill@williamguion.com)