Oaks with 30-something feet girth

In 2015, I marked 30 years that of photographing live oaks of Louisiana and 10 years since I began the 100 Oaks Project (documenting the 100 oldest oaks in Louisiana). Because of these milestones, I decided to devote 2015 to tracking down the very oldest living live oaks in Louisiana—those trees with girths of 30 feet or more. I was already familiar with a few of the more well-known oaks in this size range, but most were still on my longer list of “trees yet to find.”

To compile my list, I included all Society member trees with a circumference of 26’ feet or greater when registered. I knew from experience and from discussions with arborists that mature oaks have an average growth rate of 1” to 1.5” per year. In a half-century, a healthy live oak can easily grow three to four feet in circumference. This narrowed my search to fewer than 30 oaks in Louisiana that could potentially be in the 30-foot girth range.

Before America was America—According to several Louisiana arborists I consulted, oaks of this size are probably between 400 and 500 years of age (add another 100 years or more to this estimate for those oaks with a girth greater than 35 feet). That means these live oaks were likely growing before Europeans settled this continent (the earliest colony was established in 1565 by the Spanish in St. Augustine, Florida; Jamestown, Virginia, was established in 1607). Some were quite possibly growing before the name “America” was first used in print in 1507 as a designation for this continent—in other words, Before America was America.

The 30-something club—One New Orleans arborist I contacted about a tree’s location jokingly suggested I call my list the “30-something club.” So, I’ve incorporated that into the title of this blog entry as well and have included in this list oaks that are almost 30 feet in girth (29′-6″ or greater). To me, these venerable oaks should be recognized as cultural and historical landmarks and deserve a more significant place in public awareness—and even some minimal protection that would allow them to live to whatever ripe old age a live oak can live.

Live oak protection—Tragically, several of the oldest oaks on the Society’s registry have died, fallen off the grid of public awareness or even been removed. It’s important to note that it’s only through public awareness and human interest that a tree’s survival is secured. Currently, there are no state laws in Louisiana to protect historic or heritage trees and only spotty local ordinances that offer any protection from human removal. I’ll cover this in detail in a future blog entry.

In the next few blog entries, I’ll be documenting my search during 2015 to find these 30-something live oaks. More photos of the oldest oaks can be found at this blog entry here…

Here are the trees in order of size:

- Seven Sisters Oak – Lewisburg / Mandeville; 39′-10″

- Randall Oak – New Roads; 35′-8″

- Edna Szymoniak Oak – Hammond; 35′-6″

- Lorenzo Dow Oak – Grangeville; 35′-5″

- La Belle Coline Oak – Between Sunset and Carencro; 34’+

- The Governor’s Oak – Baton Rouge; 33′-3″

- Lastrapes Oak (Seven Brothers Oak) – Washington; 32′-3″ (largest section)

- Boudreaux Friendship Oak – Scott; 31′-10″

- Lagarde Oak – Luling; 30′-11″

- Mays Oak – Near Rosedale; 30′-11″

- Blanchet Oak – Lafayette; 30′-7″

- Grosse Tete Oak – Bayou Grosse Tete; 30′-2″

- Etienne de Bore’ Oak – Audubon Park, New Orleans; 30′

- Grenier Oak – Near Thibodaux; 29′-9″

- Josephine A. Stewart Oak – Vacherie; 29′-11″

- St. John’s Cathedral Oak – Lafayette; 29′-6″

- Stonaker Oak – New Roads; 29′-6″

- The John Hudson Oak – Prairieville, LA; 29′-6″

(This list has been updated as of December 2020)

As I continue locating and measuring additional oaks through this year, I may expand this 30-something list, but as of September, these are the oaks I’ve personally measured and confirmed to be 29′-6″ or larger.

NOTE: I’ve found a few oaks with girths stated to be larger than 29 feet on the Live Oak Society registry. However, when I measured them, their sizes were smaller. I suspect they were simply mismeasured. Those oaks are not on this list but will be mentioned in my blog entries that follow because they are still very old trees and fit into my larger 100 oldest oaks list.

A bit of background—For those readers who are new to this blog, my wife Cyndi and I began the 100 Oaks Project after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita swept across Louisiana in 2005. We started with the 43 original inductee trees listed by Dr. Edwin L. Stephens in a 1934 article he wrote for the Louisiana Conservation Review titled “In Louisiana, I saw a Live Oak Growing” (a PDF copy of that article is contained in the “Pages” section of this blog).

Dr. Stephen’s original intent was to establish an organization “to promote the culture, distribution, and appreciation of the live oak.” Members were originally limited to oaks that were at least 100 years of age, determined by a circumference of 17 feet or more, though he revised these requirements to allow registration of “junior-league” oaks with a minimum circumference of eight feet.

Each year, thousands of tourists visit St. Martinville, Louisiana, in search of the roots of Cajun culture—to experience the food, music, and to visit the places associated with the story of Evangeline. The Evangeline oak is undoubtedly the most famous oak in Louisiana, though oddly it’s not a very old or exceptionally large tree. And according to some sources, it’s the third oak in the St. Martinville area that has been designated as the “oak under which the Cajun lovers Emmeline and Louis were reunited” after their long separation when the Acadians were exiled from Canada. (Emmeline and Louis are reported to be the real-life characters upon which Longfellow’s fictitious Evangeline and Gabriel were modeled.)

Each year, thousands of tourists visit St. Martinville, Louisiana, in search of the roots of Cajun culture—to experience the food, music, and to visit the places associated with the story of Evangeline. The Evangeline oak is undoubtedly the most famous oak in Louisiana, though oddly it’s not a very old or exceptionally large tree. And according to some sources, it’s the third oak in the St. Martinville area that has been designated as the “oak under which the Cajun lovers Emmeline and Louis were reunited” after their long separation when the Acadians were exiled from Canada. (Emmeline and Louis are reported to be the real-life characters upon which Longfellow’s fictitious Evangeline and Gabriel were modeled.) The Evangeline Oak is located on the edge of Bayou Teche at the foot of East Port St., next to the Old Castillo Bed and Breakfast (which I can personally state is very haunted—but that’s another story!).

The Evangeline Oak is located on the edge of Bayou Teche at the foot of East Port St., next to the Old Castillo Bed and Breakfast (which I can personally state is very haunted—but that’s another story!).

The McDonogh Oak is the largest and oldest

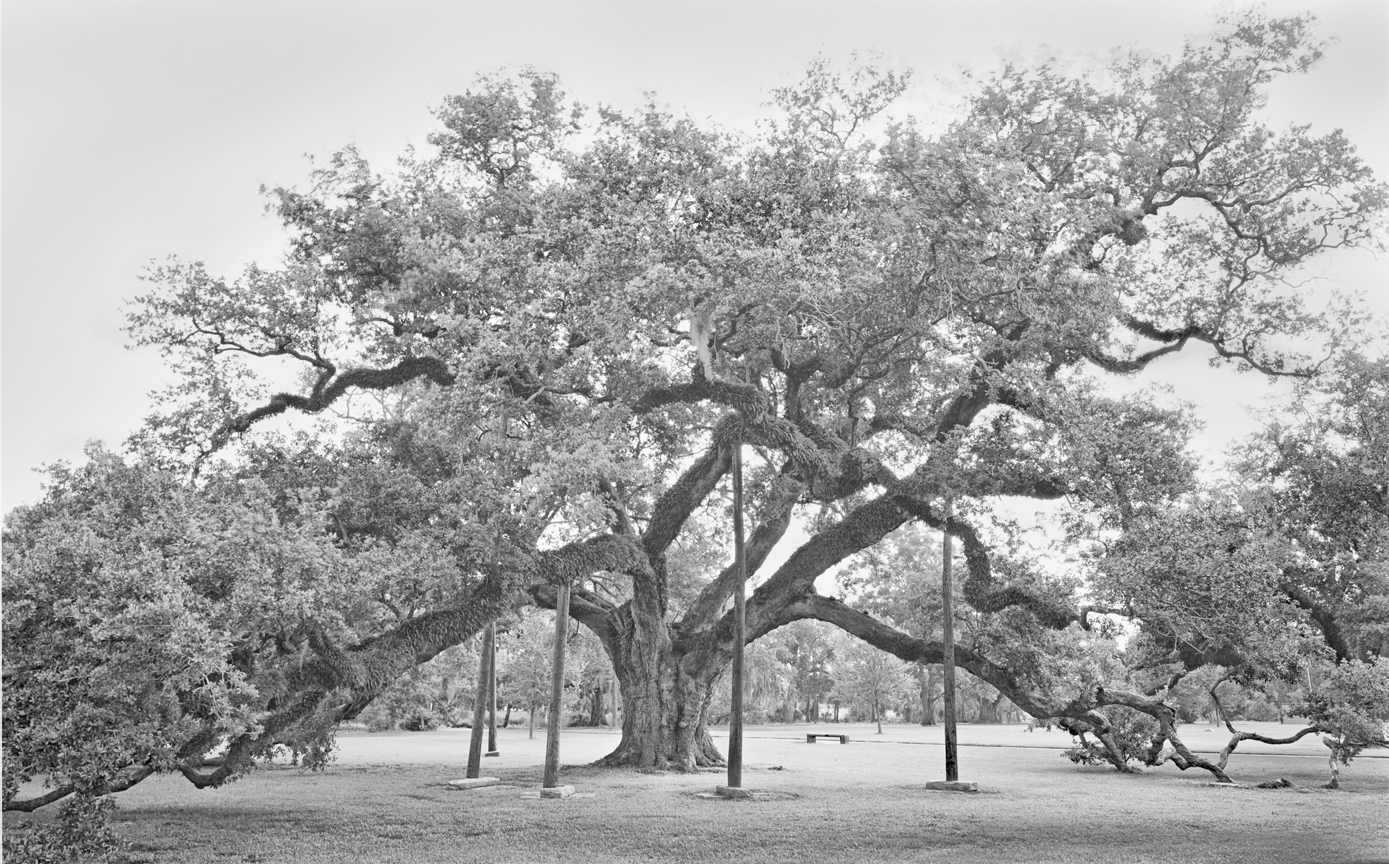

The McDonogh Oak is the largest and oldest  City Park was once part of the Jean Louis Allard Plantation, originally established in the 1770’s, and later purchased in 1845 by shipping magnate and philanthropist John McDonogh. Upon his death in 1850, McDonogh donated the land to the City of New Orleans and in 1854 a large section was designated as a city park. According to park records, in 1958, the National Park and Recreation Convention met in New Orleans and hosted a breakfast for 1,028 convention attendees under the massive canopy of the McDonogh Oak’s limbs.

City Park was once part of the Jean Louis Allard Plantation, originally established in the 1770’s, and later purchased in 1845 by shipping magnate and philanthropist John McDonogh. Upon his death in 1850, McDonogh donated the land to the City of New Orleans and in 1854 a large section was designated as a city park. According to park records, in 1958, the National Park and Recreation Convention met in New Orleans and hosted a breakfast for 1,028 convention attendees under the massive canopy of the McDonogh Oak’s limbs.