Ascension Parish and Upper River Road

Ascension Parish has always been a sort of blank spot on my live oak radar. Before I began this 30-something series, I was unaware of the number of live oaks that live there. So, I’ve been surprised and delighted to have located several old and beautiful trees that have led otherwise low-profile lives in this historic parish.

I’m not sure if I’ve emphasized enough in my earlier blogs how rare it is that 30-something-foot girth oaks have survived all of the changes that have taken place on the Louisiana landscape in the past 300 years. In her invaluable reference book, Louisiana Live Oak Lore, Ethelyn G. Orso describes the process of “live oaking,” a fairly common practice in the past in which woodsmen would cut live oaks and sell the wood to supply the wooden ship industries of Britain, France, Spain, and the United States.

Here’s an excerpt from her book on the subject:

“As early as 1709, shipwrights recognized that the near-impenetrable wood (of the live oak) was perfect for timbers and ‘knees’ for vessels. ‘Knees’ were the angular sections of wood taken from the joints between tree limbs and trunks. Such natural joints were stronger than any artificial joints made by shipwrights, and braced the sides of the ships… For the European governments that controlled Louisiana in that early colonial period, live oak wood was the state’s most prized natural resource.

Having practically deforested the European continent in search of the indispensable oak wood for their fleets, British, French, and Spanish rulers looked with greedy eyes to the vast expanses of live oak forests in the southern parts of what would become the United States. Those European governments that gained control of the part of ‘West Florida’ that today is eastern Louisiana claimed the live oak forests as state-owned resources. That led, by the mid-1770s, to a thriving illicit trade in live oak wood between the inhabitants of the area and whoever would pay for the poached wood. In 1811, after Louisiana had become a part of the United States, Louisiana Governor William C. Claiborne began communicating with the secretary of the navy in Washington, DC, and in 1817 an act was passed giving the president of the U.S. the authority to reserve lands with live oak forests for use by the U.S. Navy.”

It was hard times for large live oaks in those early years of the colony and the oaks that survived the wooden-ship era were still faced with the widespread clearing of lands for farming and ranching as well as eventual urban development. So, when I express respect and even awe at the few oaks that have managed to survive (and flourish in some cases) after 300+ years of cutting and clearing, you can understand why. Now, on to the 30-something oaks of Ascension Parish:

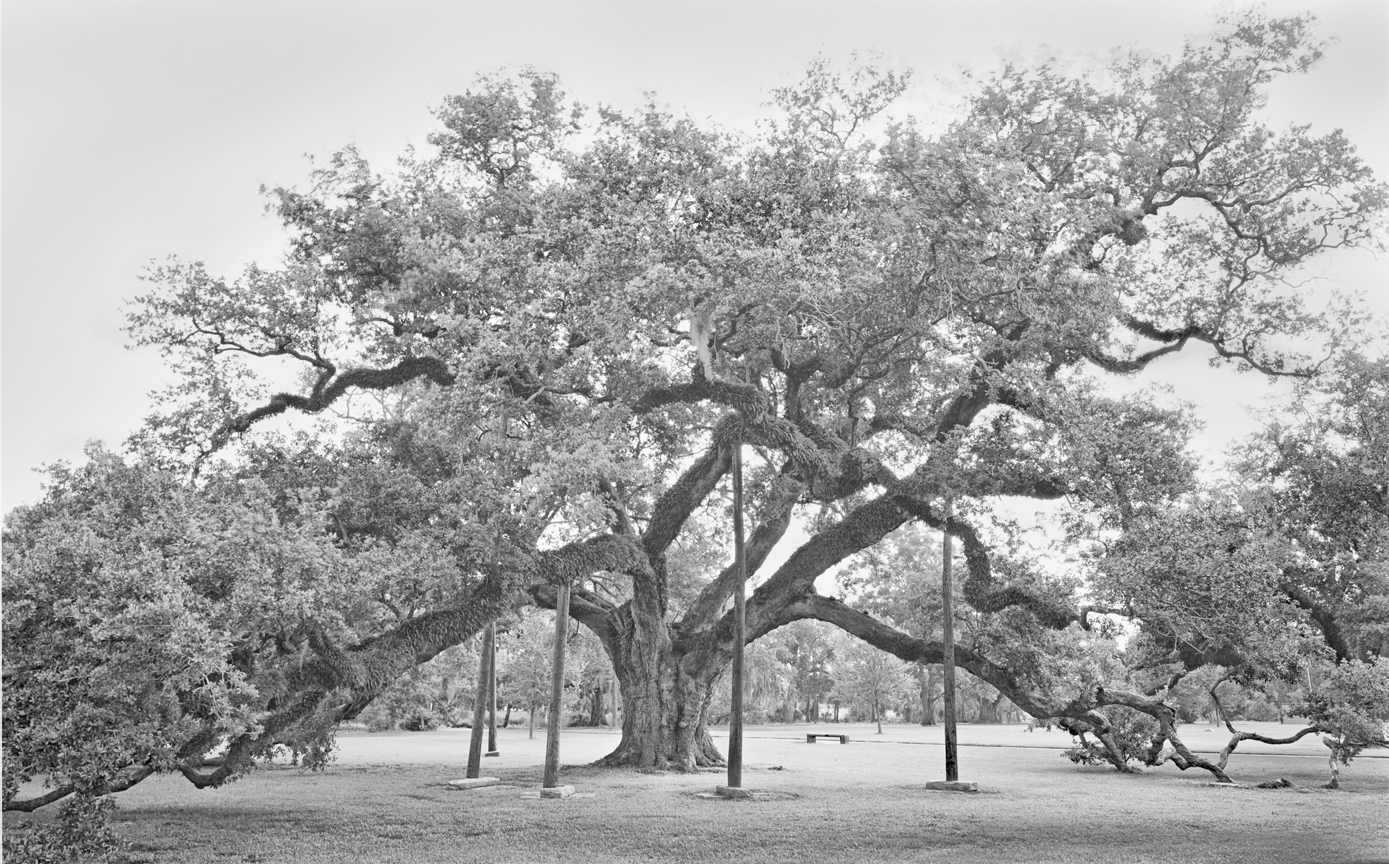

The Martin Tree—(See photos above as well) #1405 on the Live Oak Society registry, this tree was registered with a circumference of 34 feet by Ms. Delba E. Martin. She was born in 1906 and passed on in 1995. With help from the Ascension parish assessor’s office, I was able to locate the property that was once owned by Ms. Martin and the tree is still there.

The shape of the tree trunk is similar to the Rebekah Oak and others—it has a very large burled lower trunk that tapers above 5–6 ft. from the ground. Generally, this is above the 4–4.5 ft. line where one would measure the girth, but with trees like this, I take multiple measurements above and below the 4.5 ft. line and make an average measurement. My estimated girth of this oak is approximately 37’-8″ and still growing.

The John Hudson Oak is located in Prairieville, LA at the Hudson House, a beautiful historic family home that’s been in the Hudson family for several generations. The John Hudson Oak is the largest and most impressive of numerous live oaks on the grounds. It has a lovely sweeping canopy that reaches to the ground on three sides. Mrs. Ellen Hudson Waller says that several other oaks on her property are Live Oak Society members.

In my next post, I’ll include the rest of the Ascension Parish list of oaks…

Each year, thousands of tourists visit St. Martinville, Louisiana, in search of the roots of Cajun culture—to experience the food, music, and to visit the places associated with the story of Evangeline. The Evangeline oak is undoubtedly the most famous oak in Louisiana, though oddly it’s not a very old or exceptionally large tree. And according to some sources, it’s the third oak in the St. Martinville area that has been designated as the “oak under which the Cajun lovers Emmeline and Louis were reunited” after their long separation when the Acadians were exiled from Canada. (Emmeline and Louis are reported to be the real-life characters upon which Longfellow’s fictitious Evangeline and Gabriel were modeled.)

Each year, thousands of tourists visit St. Martinville, Louisiana, in search of the roots of Cajun culture—to experience the food, music, and to visit the places associated with the story of Evangeline. The Evangeline oak is undoubtedly the most famous oak in Louisiana, though oddly it’s not a very old or exceptionally large tree. And according to some sources, it’s the third oak in the St. Martinville area that has been designated as the “oak under which the Cajun lovers Emmeline and Louis were reunited” after their long separation when the Acadians were exiled from Canada. (Emmeline and Louis are reported to be the real-life characters upon which Longfellow’s fictitious Evangeline and Gabriel were modeled.) The Evangeline Oak is located on the edge of Bayou Teche at the foot of East Port St., next to the Old Castillo Bed and Breakfast (which I can personally state is very haunted—but that’s another story!).

The Evangeline Oak is located on the edge of Bayou Teche at the foot of East Port St., next to the Old Castillo Bed and Breakfast (which I can personally state is very haunted—but that’s another story!).

The McDonogh Oak is the largest and oldest

The McDonogh Oak is the largest and oldest  City Park was once part of the Jean Louis Allard Plantation, originally established in the 1770’s, and later purchased in 1845 by shipping magnate and philanthropist John McDonogh. Upon his death in 1850, McDonogh donated the land to the City of New Orleans and in 1854 a large section was designated as a city park. According to park records, in 1958, the National Park and Recreation Convention met in New Orleans and hosted a breakfast for 1,028 convention attendees under the massive canopy of the McDonogh Oak’s limbs.

City Park was once part of the Jean Louis Allard Plantation, originally established in the 1770’s, and later purchased in 1845 by shipping magnate and philanthropist John McDonogh. Upon his death in 1850, McDonogh donated the land to the City of New Orleans and in 1854 a large section was designated as a city park. According to park records, in 1958, the National Park and Recreation Convention met in New Orleans and hosted a breakfast for 1,028 convention attendees under the massive canopy of the McDonogh Oak’s limbs.