(The Leighton Plantation Oaks are located at 1801-1811 LA Hwy. 1 (St. Mary Street) about 2.5 miles north of downtown Thibodaux. The oaks are on the property between Leighton Road and Leighton Quarters Road. Turn onto Leighton Quarters Road to get the best view of the trees. The oaks range in age and size, the oldest and largest dating back to the early 1800s. There is a historic marker to Leonidas Polk at the St. Johns Episcopal Church in Thibodaux, and another (small and on the roadside) about a hundred feet north of the Leighton Quarters Road on the west side of Hwy 1.)

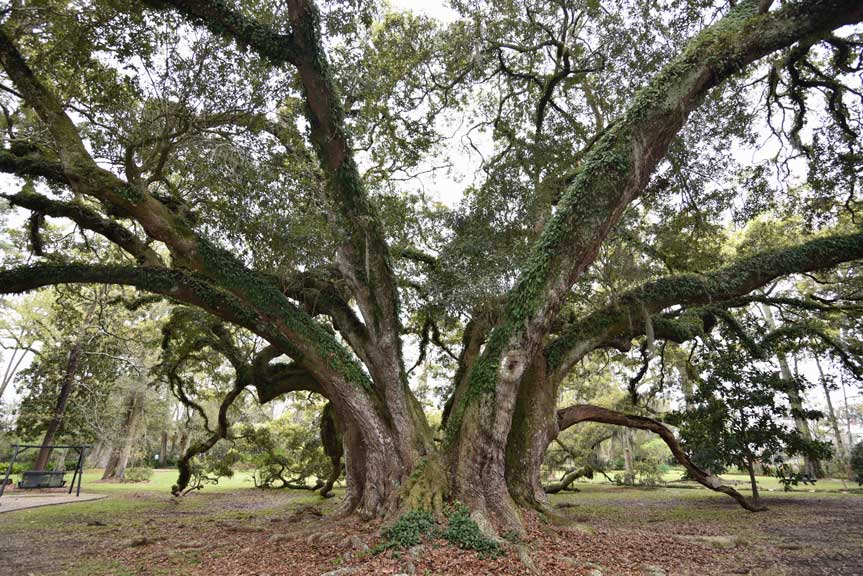

Oaks in front of current home at Leighton

There is a story that 22 of the oaks at Leighton Plantation belonged to the King of Spain in the late 1700s. As the story goes, the land grant for the property contained a stipulation that the King of Spain (Charles IV) could claim these “Royal Oaks” whenever he needed them for construction and repair of his royal navy. At the time, Spain was at war with England (1796–1808), and the wood from Louisiana’s live oaks was known worldwide to be strong enough to deflect an English cannonball.

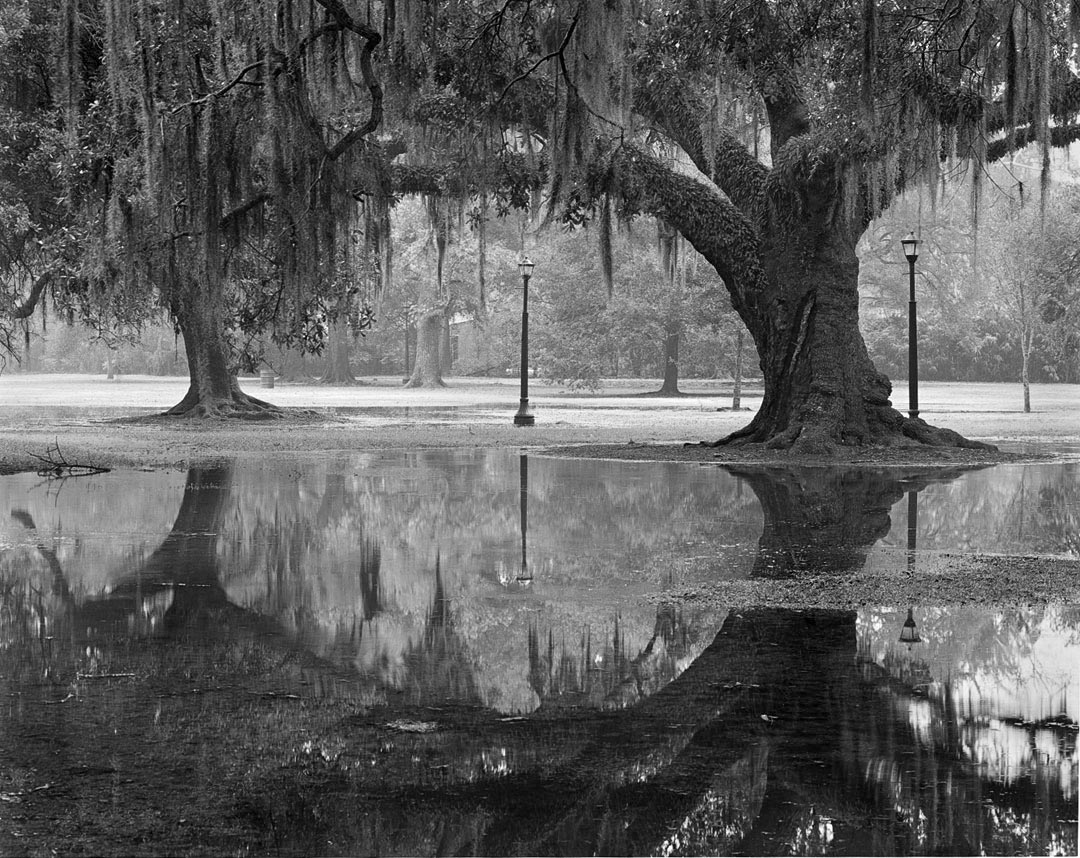

Leighton Oaks and back entry road to home

In the early 1800s, Leighton Plantation was owned by Leonidas Polk (April 10, 1806 – June 14, 1864), an Episcopal Bishop and American Confederate General. Polk was a graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point (1827). After graduation from West Point, he received special permission to resign his new commission in the U.S. Army and attend the Virginia Theological Seminary where he was ordained as an Episcopal priest. He went on to become Missionary Bishop of the Southwest in 1838 and was elected Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Louisiana in 1841.

Oak grove behind the home, Leighton Plantation

Bishop Polk established Leighton Plantation to be closer to his work as he frequently traveled between Thibodaux and New Orleans where he administered the Louisiana Episcopal Diocese from Christ Cathedral, New Orleans’ first Protestant Episcopalian church. During his tenure as bishop, he personally established St. Johns Episcopal Church in Thibodaux, Christ Church in Napoleonville, the Church of the Ascension in Donaldsonville, the Church of the Holy Communion in Plaquemine, and Trinity Church in Natchitoches. Through his crusading evangelical efforts, the Protestant Episcopal religion made a significant foothold in the predominantly Roman Catholic Louisiana.

Historic roadside marker for Leonidas Polk

Bishop Polk strongly believed in states’ rights and that the South was a “distinct cultural entity.” So after Louisiana seceded from the Union in January of 1861 and the Civil War began, he resigned as Bishop of Louisiana and took command of Confederate forces in western Tennessee. His most notable contribution to the Army of Tennessee was his calm ability to inspire confidence and religious beliefs, earning him the nickname, the “Fighting Bishop.” Polk was killed in battle in June 1864 at Pine Mountain, Georgia.

This is a mirror post from the Lafourche Live Oak Tour – which was created through the generous support of the Bayou Lafourche Convention & Visitors Bureau. View more of this blog site and share it with friends at www.liveoaktour.com.